HERBAL

MEDICINAL

PLANT

DEVIL’S CLAW

Harpagophytum procumbens (Burch.) DC ex. Meisn. (Pedaliaceae) ++

BY

RETTODWIKART THENU

DEVIL’S

CLAW

(dev’uhlz

claw)

Harpagophytum procumbens (Burch.) DC ex. Meisn. (Pedaliaceae) ++

SUMMARY AND PHARMACEUTICAL COMMENT

The

botanical name Harpagophytum means ‘hook plant’ in Greek, after the

hook-covered fruits of the plant. Devil’s claw is native to southern Africa and

has been used traditionally as a bitter tonic for digestive disturbances,

febrile illnesses and allergic reactions, and to relieve pain (Mills

& Bone 2000). It has been used in Europe for the treatment of rheumatic

conditions for over 50 years, and was first cited in the literature by Zorn at

the University of Jena, Germany, who described his observations on the

antiphlogistic and anti-arthritic effects after administration of oral aqueous

extracts prepared from the secondary roots of H. procumbens in patients

suffering from arthritides (Chrubasik et al 2006).

The chemistry of devil’s claw has been well documented. The iridoid

constituents are thought to be responsible for the reputed anti-inflammatory

activity of devil’s claw, although it is not known precisely which of these are

the most important for pharmacological activity, and the importance of other compounds.

There is conflicting evidence from in vitro, animal and human studies regarding the anti-inflammatory activity

of devil’s claw and possible mechanisms of action.

Several randomised trials using devil’s claw extracts standardised

on harpagoside content have reported superiority over placebo for some aspects

of low back pain and rheumatic complaints. However, some studies used

nonstandard outcome measures and carried out several post-hoc analyses. Further

studies have used recognised, predefined outcome measures to establish the

therapeutic value of standardised devil’s claw extracts in patients with

arthritic and rheumatic conditions.

On the basis of randomised controlled trials involving patients

with arthritic and rheumatic disorders, devil’s claw extracts appear to have a

favourable short-term adverse effect profile when taken in recommended doses.

Mild, transient gastrointestinal effects, such as diarrhoea and flatulence, may

occur. Chronic toxicity studies and clinical experience with prolonged use are

lacking, so the effects of long-term use are not known. On this basis, and in

view of the possible cardioactivity of devil’s claw, devil’s claw should not be

used for long periods of time at doses higher than recommended.

Further studies involving large numbers of patients are required.

TRADE NAMES

Devil's

Claw (available from a number of manufacturers),

Devil's

Claw Secondary Root, Devil's Claw Root Tuber

OTHER COMMON NAMES

Grapple

Plant, Wood Spider

DESCRIPTION

MEDICINAL PARTS: The medicinal

parts are the dried tubular secondary roots and the thick lateral tubers.

FLOWER AND FRUIT: The flowers grow

on short pedicles in the leaf axils and are solitary, large and foxglove-like.

The petals are pale-pink to crimson. The seed capsules are bivalvular, compressed

at the sides and ovate. The capsules are 7 to 20 cm long, 6 cm in diameter, and

very woody with longitudinally striped rind. They have a double row of elastic,

armL ike, branched appendages with an anchor-like hook. The capsules contain

about 50 dark oblong seeds with a rough surface.

LEAVES, STEM AND ROOT: The plant is

perennial and leafy. It has a branched root system and branched, prostrate

shoots 1 to 1.5 m long. The leaves are petiolate and lobed, and may be opposite

or alternate. The aerial parts of the plant die back in the dry season. The

tuber (storage) roots are formed from the main and lateral roots. The main

roots have obtuse, quadrangular, upright collar-like sections, 10 to 20 cm long

and 30 to 60 cm thick, which are covered in a fissured cork layer. The nodes of

the lateral roots are up to 60 mm thick and 20 cm long, and are light-brown to

red-brown on the outside. The roots extend out to an area of about 150 cm around

the plant and grow down to a depth of 30 to 60 cm.

CHARACTERISTICS: The dried,

pulverized secondary tubers and roots are yellowish-gray to bright pink and

horn-like in their hardness. They have a bitter taste.

HABITAT: The plant

originated in South Africa and Namibia, and has spread throughout the Savannas

and the Kalahari.

PRODUCTION: Devil's Claw root

consists of the dried lateral roots and secondary tubers of Harpagophytum

procumbens. The lateral roots are cut into slices or pieces, or pulverized immediately

after digging because they harden and become very difficult to cut once dry.

SPECIES (FAMILY)

Harpagophytum procumbens (Burch.) DC ex. Meisn.

(Pedaliaceae) ++

SYNONYM(S)

Uncaria procumbens Burch.

Harpagophytum, Harpagophytum burchelii Decne, Grapple Plant,

Wood Spider

ORIGIN

Devil’s claw grows wild in

southwest Africa.

PHARMACOPODIAL AND OTHER MONOGRAPHS

BHC 1992(G6)

BHMA 2003(G66)

BHP 1996(G9)

BP 2007(G84)

Complete German Commission E(G3)

ESCOP 2003(G76)

Martindale 35th edition(G85)

Ph Eur 2007(G81)

LEGAL CATEGORY (LICENSED PRODUCTS)

Devil's claw is not included in the GSL.(G37)

CONSTITUENTS

See

also General Reference G2.

Carbohydrates

Fructose, galactose, glucose and myo-inositol (monosaccharides), raffinose,

stachyose (46%) and sucrose (oligosaccharides).(1)

Diterpenes

(þ)-8,11,13-totaratriene-12,13-diol and (þ)-8,11,13- abietatrien-12-ol.(2)

Iridoids

Harpagoside (1–3%), harpagide, 8-p-coumaroylharpagide, 8-feruloylharpagide,

8-cinnamylmyoporoside, 60-O-p-coumaroylharpagide, 60-p-coumaroylprocumbide, and

pagoside.(3–5) p-Coumaroyl esters occur as E and Z isomers.(5)

Phenylpropanoids

Acteoside and isoacteoside, 6-O-acetylacteoside,( 4–6)

2,6-O-diacetylacteoside.(7)

Other Constituents Amino acids, flavonoids

(e.g. kaempferol, luteolin), triterpenoids, sterols.(4, G75)

Other Plant Parts The flower, stem and ripe fruit are reported to be devoid of

harpagoside; the leaf contains traces of iridoids.(8)

Quality Of Plant Material and

Commercial Products

According to the British and European Pharmacopoeias, devil's claw

root consists of the cut and dried tuberous secondary roots of H. procumbens DC. It contains not less

than 1.2% of harpagoside, calculated with reference to the dried drug.(G81,

G84) As with other herbal medicinal products, there is variation in the qualitative

and quantitative composition of commercial devil's claw root preparations.

Some commercial extracts of devil's claw root may have been prepared

not only from the roots of H. procumbens, but also from the roots of H.

zeyheri, which are similar macroscopically.(9) However, the two species differ

in the concentration of the constituents harpagoside and 8-p-coumaroylharpagide.

On this basis it has been stated that the species can be distinguished chemically

by determining the ratio harpagoside : 8-p-coumaroylharpagide.

The ratio is stated to be near one for H. zeyheri and between 20

and 38 for H. procumbens which has a

low 8-pcoumaroylharpagide content.(9) While this ratio may be sufficient for

chemotaxonomic differentiation, it may not be adequate for quality control.(10)

Other studies have demonstrated that the harpagoside content of

several powdered dry extracts of devil's claw from different manufacturers

varies, and that each extract has a unique profile of other constituents.(11)

The harpagoside content of commercial extracts of H. procumbens has been reported to range from 0.8– 2.3%.(12)

COMPOUNDS

Liridoide

monoterpenes: including

harpagoside (extremely bitter), harpagide, procumbide

Phenylethanol

derivatives: including

acteoside (verbascoside); isoacteoside

Oligosaccharides:

stachyose

Harpagoquinones (traces)

CHEMICAL COMPONENTS

The major active constituent is considered to be the bitter iridoid

glucoside, harpagoside, which should constitute not less than 1.2% of the dried

herb. Other iridoid glycosides include harpagide, procumbide, 8-O-(p-coumaroyl)-harpagide

and verbascoside. About 50% of the herb consists of sugars. There are also

triterpenes, phytosterols, plant phenolic acids, flavonol glycosides and

phenolic glycosides. Harpagophytum zeyheri, which has a lower level of

active compounds, may be partially substituted for H. procumbens in some

commercial preparations (Stewart & Cole 2005).

The extraction solvent (e.g. water, ethanol) has a major impact on

the active principle of the products (Chrubasik 2004a).

When administering H. procumbens extract topically it was found that

higher penetration of all compounds occurred from an ethanol/water preparation (Abdelouahab

& Heard 2008b).

USES

USES

Devil’s claw is used to increase the appetite and to

treat joint pain and infl ammation, arthritis, allergies, headache, heartburn,

dysmenorrhea, gastrointestinal upset, malaria, gout, and nicotine poisoning.

FOOD USE

Devil's

claw is not used in foods.

HERBAL USE

Devil's

claw is stated to possess anti-inflammatory, antirheumatic, analgesic, sedative

and diuretic properties. Traditionally, it has been used as a stomachic and a

bitter tonic, and for arthritis, gout, myalgia, fibrositis, lumbago,

pleurodynia and rheumatic disease.(G2, G6–G8,G32, G64) Modern use of devil's

claw is focused on its use in the treatment of rheumatic and arthritic

conditions, and low back pain.

CLINICAL USE

Arthritis

Overall, evidence from clinical trials suggests that devil’s claw

is effective in the treatment of arthritis. An observational study of 6 months’

use of 3–9 g/day of an aqueous extract of devil’s claw root reported significant

benefit in 42–85% of the 630 people suffering from various arthritic complaints

(Bone & Walker 1997). In a 12-week uncontrolled

multicentre study of 75 patients with arthrosis of the hip or knee, a strong

reduction in pain and the symptoms of osteoarthritis were observed in patients taking

2400 mg of devil’s claw extract daily, corresponding to 50 mg harpagoside

(Wegener & Lupke 2003). Similar results were reported in a 2-month observational

study of 227 people with osteoarthritic knee and hip pain and non-specific low

back pain (Chrubasik et al 2002) and a double-blind study

of 89 subjects with rheumatic complaints using powdered devil’s claw root (2 g/day)

for 2 months, which also provided significant pain relief, whereas another

double-blind study of 100 people reported benefit after 1 month (Bone

& Walker 1997).

A case report suggests that devil’s claw relieved strong joint

pain in a patient with Crohn’s disease (Kaszkin et al 2004b). A single group

open study of 8 weeks duration involving 259 patients showed statistically significant

improvements in patient assessment of global pain, stiffness and function, and

significant reductions in mean pain scores for hand, wrist, elbow, shoulder,

hip, knee and back pain. Moreover, quality of life scores significantly

increased and 60% of patients either reduced or stopped concomitant pain

medication (Warnock et al 2007).

Comparisons with standard treatment have also been investigated. In

2000, encouraging results of a randomised double-blind study comparing the effects

of treatment with devil’s claw 2610 mg/day with diacerhein 100 mg/day were

published (Leblan et al 2000). The study involved 122 people with osteoarthritis of the hip

and/or knee and was conducted over 4 months. It found that both treatment groups

showed similar considerable improvements in symptoms of osteoarthritis;

however, those receiving devil’s claw required fewer rescue analgesics. One

double-blind, randomised, multicentre clinical study of 122 patients with

osteoarthritis of the knee and hip found that treatment with Harpadol (6

capsules/day, each containing 435 mg of cryoground powder of H. procumbens)

given over 4 months was as effective as diacerhein (an analgesic) 100 mg/day (Chantre

et al 2000). However, at the end of the study, patients taking Harpadol were

using significantly fewer NSAIDs and had a significantly lower frequency of

adverse events. In a 6-week study of only 13 subjects, similar benefits for

devil’s claw and indomethacin were reported (Newall et al 1996). A preliminary

study comparing the proprietary extract Doloteffin with the COX-2 inhibitor

rofecoxib reported a benefit with the herbal treatment but suggested that

larger studies are still required (Chrubasik et al 2003b). Previously

reviews have concluded that there is moderate evidence of the effectiveness of H.

procumbens in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the spine, hip and knee; however it is suggested, as with many herbal

medicines, that evidence of effectiveness is not transferable from product to

product and that the evidence is more robust for

products that contain at least 50 mg of harpagoside in the

daily dosage (Chrubasik et al 2003a, Gagnier et al

2004, Long et al 2001).

Recently two reviews have concluded that ‘data from higher quality

studies suggest that Devil’s claw appeared effective in the reduction of the

main clinical symptom of pain’ (Brien et al 2006) and that the evidence of effectiveness was ‘strong’ for at least

50 mg of harpagoside as the daily dose (Chrubasik JE et al 2007). Nevertheless,

2 other recent reviews concluded that there was only ‘limited evidence’ (Ameye & Chee 2006) and

‘insufficient reliable evidence’ regarding the long term effectiveness of devil’s

claw (Gregory et al 2008).

The herb is Commission E approved as supportive therapy for

degenerative musculoskeletal disorders (Blumenthal

et al 2000) and ESCOP approved for painful

osteoarthritis (ESCOP 2003).

Back

pain

Several double-blind studies have reported benefit with devil’s

claw in people with back pain. A doubleblind study of 117 people with back pain

reported decreased pain and improved mobility after 8 weeks’ treatment with devil’s

claw extract LI 174, known commercially as Rivoltan (Laudahn

& Walper 2001).

Use of the same extract provided significant pain relief after 4

weeks in another randomised, doubleblind placebo-controlled study of 63

subjects with muscle stiffness (Gobel et al 2001).

Similar results were reported in two double-blind studies of 118 people (Chrubasik

et al 1996) and 197 people (Chrubasik et

al 1999) with chronic lower back pain.

Devil’s claw appears to compare favourably to conventional treatments.

A 6-week double-blind study of 88 subjects comparing devil’s claw to rofecoxib found

equal improvements in both groups (Chrubasik et al 2003b) A

follow-up of the subjects from that study who were all given devil’s claw for 1

year found that it was well tolerated and improvements were sustained (Chrubasik

et al 2005). In an open, prospective study, an unspecific lower back pain

treatment with Harpagophytum extract and conventional therapy were found

to be equally effective (Schmidt et al 2005).

Three recent reviews looking at the treatment of low back pain

concluded that there is strong evidence for short-term improvements in pain and

rescue medication for devil’s claw products standardised to 50 and 100 mg

harpagoside as daily doses (Chrubasik JE et al 2007, Gagnier

et al 2006, 2007). Devil’s claw root is approved for relief of low back pain

by ESCOP (ESCOP 2003).

Dyspepsia

Traditionally, devil’s claw has also been used to treat dyspepsia

and to stimulate appetite (Fisher & Painter

1996). The bitter principles in the herb provide a theoretical basis

for its use in these conditions, although controlled studies are not available to

determine effectiveness. The herb is Commission E (Blumenthal

et al 2000) and ESCOP (2003) approved for dyspepsia and loss of appetite.

OTHER USES

Traditionally, the herb is also used internally to treat febrile

illnesses, allergic reactions and to induce sedation, and topically for wounds,

ulcers, boils and pain relief (Fisher & Painter 1996, Mills &

Bone 2000), as well as for diabetes, hypertension, indigestion and anorexia

(Van Wyk 2000).

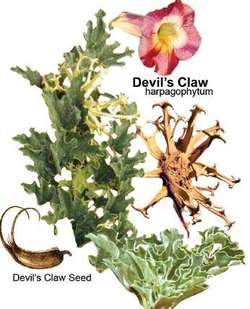

Figure 1. Devil’s

claw (Harpagophytum procumbens).

Figure 2. Devil’s claw – dried drug substance (root).

ACTIONS

Antiinflammatory

Action

Several studies have evaluated

the antiinfl ammatory properties of devil’s claw in the treatment of joint

conditions. The results are mixed. One Canadian study (Whitehouse et al, 1983)

evaluated Harpagophytum

procumbens for reduction of rat hindfoot edema.

Devil’s claw was completely ineffective, even at doses greater than 100 times the

recommended human dose. Another study produced similar results. No clinical signifi

cance was found when human subjects consumed devil’s claw (Moussard et al, 1992).

Another study (Baghdikian et al, 1997) reported confl icting results on

harpagoside, one of the chemical components of the herb, which showed analgesic

and antiinfl ammatory properties. H. procumbens was found to produce analgesic and antiinfl ammatory

effects (Chantre et al, 2000; Fiebich et al, 2001; Gobel et al, 2000).

Another study determined that

the iridoid glycosides are responsible for the analgesic, antiinfl ammatory,

and antiphlogistic effects of devil’s claw (Wegener, 1999). Devil’s claw

possesses analgesic, antiinfl ammatory, and hypoglycemic properties as

suggested in folklore (Mahomed, 2004).

Cardiovascular

Action

When rats and rabbits were

studied to determine the cardiovascular effects of H. procumbens, a signifi cant dose-dependent reduction occurred in

arterial blood pressure, along

with a reduction in heart rate at high doses. Harpagoside, one of the chemical components of the herb, exhibited less activity than

did the extract of H.

procumbens.

The extract of H. procumbens produced a mild decrease in heart rate, with mild

positive inotropic effects at low doses but a signifi cant negative inotropic

effect at higher doses. Harpagoside showed negative chronotropic and positive

inotropic effects (Circosta et al, 1984). Another study demonstrated that

devil’s claw exerts a protective action in hyperkinetic ventricular arrhythmias

in rats (Costa De Pasquale et al, 1985).

Other Actions

Devil’s claw depresses the central nervous system and may

be used as an anticoagulant as described in folklore (Mahomed, 2006).

PHARMACOLOGICAL ACTIONS

The active constituents of devil's claw are widely held to be

the iridoid glucosides although, of these, it has not been definitively established

whether harpagoside is the most important pharmacologically active constituent

of the whole extract. Other compounds present in the root may contribute to the

pharmacological activities of devil's claw.(15, 16) It has also been suggested that

harpagogenin, formed by in vivo acid hydrolysis of harpagoside, may have

biological activity.(17)

IN VITRO AND ANIMAL STUDIES

Pharmacokinetics Transformation of the iridoids harpagide, harpagoside

and 8-O-(p-coumaroyl)-harpagide into the pyridine monoterpene alkaloid aucubinine

B, chemically or by human intestinal bacteria in vitro, has been documented.(18,

19) However, it is not known if aucubinine B is formed in vivo by intestinal bacteria

and, therefore, whether it contributes to the pharmacological activity of

devil's claw.(19)

Anti-inflammatory and analgesic

activities Animal studies of the

anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities of devil's claw have reported conflicting results. Activity appears to differ

depending on the route of administration of devil's claw, and the model of inflammation,

whether acute or subacute. Also, studies have assessed the effects of different

preparations of H. procumbens (e.g.

aqueous extracts and ethanolic extracts) and it is important to consider this

when interpreting the results.

In controlled experiments in rats, a 60% ethanol extract of H. procumbens roots injected

(compartment and site not specified) at doses of 25, 50 and 100 mg/kg body

weight daily for four days beginning five days after sub-plantar injection of

Freund's adjuvant produced a significantly greater antinociceptive response in

the hot-plate test and significantly reduced paw oedema than did control

(distilled water) on days 6–8 after induction of experimental arthritis (p <

0.01 for all).(20) Similar results were obtained when administration of H. procumbens extract was initiated 20

days after sub-plantar injection of Freund's adjuvant and continued for 20

days, with tests for antinociceptive and antiinflammatory activity performed on

four occasions during this period. Pretreatment with a dried aqueous extract of

devil's claw root at doses of 100 mg/kg and above, administered

intraperitoneally, resulted in peripheral analgesic activity demonstrated by a significant

reduction in the number of writhings induced by acetic acid in mice.(16)

However, no effect was observed in the hotplate test, indicating a lack of central

analgesic activity with devil's claw extract.

The peripheral analgesic properties of intraperitoneal dried aqueous

extract of devil's claw have been confirmed in other studies for doses of 400

mg/kg and above.(9) A subsequent series of experiments found that administration

of an aqueous extract of H. procumbens root

at doses of 200–800 mg/kg body weight intraperitoneally resulted in significantly

greater antinociceptive effects than did control in both the hot-plate and

acetic-acid induced writhings tests in mice (p < 0.05 versus control) and,

at a dose of 400 or 800 mg/kg body weight, in a significant reduction in

egg-albumin induced hind-paw inflammation in rats, compared with control (p

< 0.05).(21)

In contrast, other studies have reported that dried aqueous extract

of devil's claw administered orally had no effect on carrageenan- or

Mycobacterium butyricum- (Freund's adjuvant) induced oedema in rat paw, whereas

both indometacin and aspirin displayed significant anti-inflammatory

activity.(22, 23) However, dried aqueous extract of devil's claw administered

by intraperitoneal injection demonstrated significant activity in the

carrageenan- induced oedema test in rats, an acute model of inflammation.(16)

The effect on oedema was dose-dependent for doses of devil's claw extract

100–400 mg/kg, and reached a maximum three hours after carrageenan injection.

Other studies in rats have reported significant reductions in oedema using the same

model following pretreatment with intraperitoneal(9, 24) and intraduodenal, but

not oral, dried aqueous extract of devil's claw.(24)

Anti-inflammatory activity of harpagoside has been demonstrated in

experimental models, including the croton oil-induced granuloma pouch test, and

for harpagogenin, the aglucone of harpagoside, in the croton oil-induced

granuloma pouch test and in formalin-induced arthritis in rats.(25) Studies

have also reported peripheral analgesic and antiinflammatory properties for the

related species Harpogophytum zeyheri.(9) Animal studies using aqueous extracts

of devil's claw have suggested that the extract may be inactivated by passage through

the acid environment of the stomach.(16, 24) One study compared the

anti-inflammatory activities of aqueous devil's claw extract administered by

different routes. Intraperitoneal and intraduodenal administration led to a

significant reduction in the carrageenan-induced rat paw oedema test, but there

was no effect following oral administration.(24) In another study, aqueous devil's

claw extract pretreated with hydrochloric acid to mimic acid conditions in the

stomach showed no activity in pharmacological models of pain and

inflammation.(16)

A clear mechanism of action for the purported anti-inflammatory effects

of devil's claw has yet to be established. In vitro, devil's claw (100 mg/mL )

had no significant effect on prostaglandin (PG) synthetase activity, whereas

indometacin (316 mg/mL ) and aspirin (437 mg/mL ) caused 50% inhibition of this

enzyme.(23) In other in vitro studies in human whole blood samples, devil's

claw extracts and fractions of extracts were tested for their effects on thromboxane

B2 (TXB2) and leukotriene (LT) biosynthesis.(26) TXB2 is an end-product of arachidonic

acid metabolism by the cyclooxygenase 1 (COX-1) pathway. Inhibition appeared to

be dependent on the harpagoside content of the extracts or fractions.(26) An

aqueous extract of H. procumbens inhibited

lipopolysaccharide-induced enhancement of cyclooxygenase-2 activity, resulting

in suppression of PGE2 synthesis in in-vitro experiments using the mouse fibroblast

cell line L929.(27) In the same system, the extract inhibited inducible nitric

oxide synthase (iNOS) mRNA expression, resulting in suppression of nitric oxide

production. Inhibition of iNOS expression by an aqueous extract of H. procumbens roots, resulting in

suppression of nitrite production, has also been described following

experiments in rat renal mesangial cells. The effect was observed with a

harpagoside free extract and with an extract containing a high concentration (27%)

of harpagoside, but not with extracts containing around 2% harpagoside,

indicating that high concentrations of harpagoside as well as other

concentrations are necessary to bring about the effect.(28)

Harpagoside (100 mmol/L), but not harpagide (100 mmol/L), inhibited

calcium ionophore A23187-stimulated release of TXB2 from human platelets.(29)

However, harpagoside and harpagide had no significant inhibitory effect on

calcium ionophore A23187-stimulated release of PGE2 and LTC4 from mouse

peritoneal macrophages.(29)

Other preclinical studies have described effects for devil's claw

extracts and/or isolated constituents on other pathways involved in

inflammatory processes. In vitro inhibition of tumour-necrosisfactor- a (TNF-a)

synthesis in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human monocytes by a hydroalcoholic

extract of devil's claw (SteiHap 69) has also been documented.(30) Inhibitory

activity against human leukocyte elastase (a serine proteinase involved in inflammatory

processes) has been reported for an aqueous extract of H. procumbens roots (drug to extract ratio 1.5-2.5 : 1) and the isolated

constituents 60-O-acetylacteoside, isoacteoside, 8-p-coumaroylharpagide, pagoside

and caffeic acid, with IC50 values of 542, 47, 179, 179, 154 and 86 mg/mL ,

respectively. The IC50 values for several other constituents, including

acteoside and harpagoside were higher than 300 mg/mL (4). An ethanol extract of H. procumbens

significantly reduced IL-1b-induced production of several matrix metalloproteinase

enzymes (MMPs) in human chondrocytes.(31) (In inflammatory diseases, there is

increased production of cytokines such as IL-1b and TNF-a, which results in an

increased production of MMPs which breakdown the extracellular cartilage

matrix.)

Other activities

Crude methanolic extracts of devil's claw have been shown to be cardioactive in

vitro and in vivo in animals. A protective action against ventricular

arrhythmias induced by aconitine, calcium chloride and epinephrine

(adrenaline)/chloroform has been reported for devil's claw given

intraperitoneally or added to the reperfusion medium.(32, 33) The crude extract

was found to exhibit greater activity than pure harpagoside.(33) In isolated

rabbit heart, low concentrations of a crude methanolic extract had mild

negative chronotropic and positive inotropic effects,(32) whereas high

concentrations caused a marked negative inotropic effect with reduction in

coronary blood flow.(32) In anaesthetised dogs, harpagoside administered orally

by gavage caused a decrease in mean aortic pressure and arterial and pulmonary

capillary pressure.(34)

In vitro, harpagoside has been shown to decrease the contractile

response of smooth muscle to acetylcholine and barium chloride on guinea-pig

ileum and rabbit jejunum. Harpagide was found to increase this response at

lower concentrations, but antagonised it at higher concentrations.(35) On the

basis of these studies in isolated smooth muscle, it was suggested that the

constituents of devil's claw may influence mechanisms regulating calcium influx.(35)

Methanolic extracts have also exhibited hypotensive properties in

normotensive rats, causing a decrease in arterial blood pressure following oral

doses of 300 mg/kg and 400 mg/kg body weight.(32) Aqueous fractions derived

from an extract of devil's claw root (drug to extract ratio 2 : 1 containing

2.6% harpagoside) showed antioxidant activity in an in-vitro assay based on

ability to scavenge 2,20-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)-derived

radicals.(36) However, harpagoside showed only weak antioxidant activity. In

mice, a methanol extract of H. Procumbens root tubers applied topically to

shaven skin 30 minutes before application of 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate

(TPA), a stimulator of COX-2 expression, led to a significant reduction in

COX-2 protein when assessed four hours after TPA administration.(37) The

extract did not have any effect on TPA-induced activation of nuclear factor-kB,

but inhibited TPA-induced activation of activator protein-1, which is involved

in the regulation of COX-2 in mouse skin. Overexpression of COX-2 is thought to

be involved in tumour promotion. Antidiabetic activity has been described for

an aqueous extract of H. procumbens root

in in vivo experiments in rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes mellitus.(21)

The extract significantly reduced blood glucose concentrations in both fasted normoglycaemic

rats and fasted diabetic rats when administered intraperitoneally at doses of

800 mg/kg body weight. T

wo diterpene constituents ((þ)-8,11,13-totaratriene-12,13-diol and

(þ)-8,11,13-abietatrien-12-ol) isolated using bioassay-guided fractionation

from a petroleum ether extract of H.

procumbens root were found to be active against a chloroquine-sensitive

(D10) and a chloroquine-resistant (K1) strain of Plasmodium falciparum in vitro (IC50 < 1 mg/mL ).(2)Devil's claw

extracts possess weak antifungal activity against Penicillium digitatum and Botrytis

cinerea.(38)

CLINICAL STUDIES

Pharmacokinetics

There is little published information on the pharmacokinetics of devil's claw

extracts in humans. A pharmacokinetic study involving a small number of healthy

male volunteers (n = 3) measured plasma harpagoside concentrations after oral

administration of devil's claw extract (WS1531 containing 9% harpagoside) 600, 1200

and 1800 mg as film-coated tablets.(26) Maximal plasma concentrations of

harpagoside were reached after 1.3–1.8 hours, and were 8.2 ng/mL and 27.8 ng/mL for doses of harpagoside of 108 and 162 mg,

respectively (corresponding to 1200 and 1800 mg devil's claw extract, respectively).

Other studies involving small numbers of healthy male volunteers indicated that

the half-life ranged between 3.7 and 6.4 hours. Other results suggested that

there may be low oral absorption or a considerable first-pass effect with

devil's claw extract, although this needs further investigation.(26)

Pharmacodynamics A

study involving healthy volunteers investigated the effects on eicosanoid

production of orally administered devil's claw (four 500-mg capsules of powder,

containing 3% glucoiridoids, daily for 21 days).(39) No statistically significant

differences on PGE2, TXB2, 6-keto-PGF1a and LTB4 were observed following the

period of devil's claw administration, compared with baseline values. By

contrast, in a subsequent study involving whole blood samples taken from

healthy male volunteers, a biphasic decrease in basal cysteinyl-leukotriene

(Cys-LT) biosynthesis, compared with baseline values, was observed following

oral administration of devil's claw extract (WS1531 containing 9% harpagoside)

600, 1200 and 1800 mg as film-coated tablets.(26)

Therapeutic activity

The efficacy and effectiveness of devil's claw have been investigated in around

20 clinical studies involving patients with rheumatic and arthritic conditions,

and low back pain.(15, 40) These studies have involved different methodological

designs, including several uncontrolled studies, and different preparations of

devil's claw, including crude drug and aqueous extracts. Evaluating the evidence

is further complicated as preparations tested in clinical trials typically have

been standar-dised for their harpagoside content and, although harpagoside is believed

to contribute to activity, it is not yet clear to what extent and which other

constituents are important. Therefore, at present, there is insufficient

evidence to draw definitive conclusions regarding the efficacy of specific

devil's claw preparations, and because of the differences in the pharmaceutical

quality of individual preparations, general conclusions on efficacy cannot be drawn.(41)

A systematic review of the quality of clinical trials involving devil's

claw found that although the results of some studies have provided evidence for

the effectiveness of certain devil's claw preparations, the quality of evidence

was not sufficient to support the use of any of the available products.(42)

A systematic review of 12 controlled, randomised or

quasirandomised trials of H. procumbens preparations

in patients with osteoarthritis (5 trials), low back pain (4 trials) and mixed

pain conditions (3 trials) found differing levels of evidence for the different

H. procumbens preparations assessed.

There was evidence (from two trials involving a total of 325 participants) that

an aqueous extract of H. procumbens administered

orally at a dose equivalent to harpagoside 50 mg daily for four weeks was superior

to placebo in reducing pain in patients with acute episodes of chronic

non-specific low-back pain.(13) There was also evidence (from one trial for

each) that the same extract administered orally at a dose equivalent to

harpagoside 100 mg daily for four weeks was superior to placebo, and at a dose

equivalent to harpagoside 60 mg daily for six weeks was not inferior

to rofecoxib 12.5 mg daily, in reducing pain in patients with acute episodes of

chronic non-specific low-back pain. There was evidence that powdered H. procumbens plant material at a dose

equivalent to 57 mg harpagoside daily for 16 weeks was not inferior to

diacerhein. Overall, however, the limited amount of data and heterogeneous

nature of the available studies, indicate that further randomised controlled

trials assessing well-characterised H.

procumbens preparations and involving sufficient numbers of patients are

required. Several of the trials mentioned above are discussed in more detail

below. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study involving 118

patients with acute exacerbations of chronic low back pain investigated the

effects of devil's claw extract 800 mg three times daily (equivalent to 50 mg

harpagoside daily) for four weeks.(43) There was no statistically significant

difference between the devil's claw and placebo groups in the primary outcome

measure –consumption of the opioid analgesic tramadol over weeks 2–4 of the

study – among the 109 patients who completed the study. This was an unusual

choice of primary outcome measure as it gives no direct indication of the

degree of pain experienced by participants. There was a trend towards improvement

in a modified version of the Arhus Low Back Pain Index (a measure of pain,

disability and physical impairment) for devil's claw recipients compared with placebo

recipients, although this did not reach statistical significance. A greater

proportion of patients in the devil's claw group were pain-free at the end of

the study, although this was only a secondary outcome measure.

On the basis of these findings, a subsequent randomised, double-blind,

placebo-controlled trial involving 197 patients with exacerbations of low back

pain tested the effects of two doses of devil's claw (WS1531) extract against

placebo.(44) Participants received devil's claw extract 600 mg or 1200 mg daily

(equivalent to 50 mg and 100 mg harpagoside daily, respectively), or placebo,

for four weeks. There was a statistically significant difference (p =0.027)

between devil's claw and placebo with respect to the primary outcome measure – the

number of patients who were pain-free without tramadol for at least five days

during the last week of the study. However, numbers of patients who were

painfree were low (3, 6 and 10 for placebo, devil's claw 600 mg daily and

devil's claw 1200 mg daily, respectively). Furthermore, this is a non-standard

outcome measure. Arhus Low Back Pain Index scores improved significantly in all

three groups, compared with baseline values, although there was no

statistically significant difference between groups.

In a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study involving

patients with non-specific low back pain, 65 participants received devil's claw

extract (LI-174, Rivoltan), or placebo, 480 mg twice daily (equivalent to 24 mg

harpagoside daily) for four weeks.(45) There was a significant improvement (p

< 0.001) in visual analogue scale (VAS) scores for muscle pain in the

devil's claw group, but not the placebo group, compared with baseline values,

after two and four weeks' treatment. Differences in VAS scores between the two

groups were statistically significant after four weeks' treatment (p <

0.001). Significant differences between the two groups in favour of devil's claw

after four weeks' treatment were also observed with several other parameters,

including muscle stiffness and muscular ischaemic pain.

A small number of studies has compared the efficacy of devil's claw

with that of conventional pharmaceutical agents in the treatment of low back

pain. In a randomised, double-blind, pilot trial, 88 participants with acute

exacerbations of low back pain received an aqueous extract of devil's claw

(Doloteffin; drug to extract ratio 1.5-2.5:1) 2400 mg daily in three divided

doses (equivalent to 60 mg harpagoside daily), or rofecoxib (Vioxx) 12.5 mg

daily for six weeks.(46) At the end of this period, compared with baseline

values, there were improvements in Arhus Low Back Pain Index scores, health

assessment questionnaire scores, and increases in the numbers of pain-free

patients for both groups. There were no statistically significant differences

between groups for any of the outcome measures but, because the study did not

include sufficient numbers of patients, these findings do not demonstrate

clinical equivalence between the two treatments.(46)

A randomised, double-blind, pilot trial in which 88 participants

with acute exacerbations of low back pain received an aqueous extract of

devil's claw (Doloteffin), or rofecoxib (Vioxx) for six weeks offered

participants continuing treatment with devil's claw aqueous extract two tablets

three times daily for up to one year after the six-week pilot study. Participants

were not aware of their initial study group (i.e. devil's claw extract or

rofecoxib) until towards the end of the one-year follow-up study.(47) In total,

38 and 35 participants who had previously received devil's claw and rofecoxib,

respectively, participated in the follow-up study, and underwent assessment

every six weeks. After 24 and 54 weeks, 53 and 43 participants, respectively,

remained in the study. There were no convincing differences between the two

groups (i.e. those who previously received devil's claw and those who received

rofecoxib) with respect to pain scores, use of additional analgesic medication,

Arhus Index scores and health assessment questionnaire scores.

Furthermore, the uncontrolled design of the follow-up study would

have precluded any definitive conclusions regarding differences between the two

groups. A randomised, double-blind trial compared the efficacy of devil's claw

extract with that of diacerein in 122 patients with osteoarthritis of the knee

and hip.(14) Participants received powdered cryoground devil's claw (Harpadol)

2.61 g daily, or diacerein 100 mg daily, for four months.

VAS scores for spontaneous pains improved significantly in both

groups, compared with baseline values, and there were no differences

between devil's claw and diacerein with respect to VAS scores.

In a placebo-controlled study involving 89 patients with rheumatic

complaints, devil's claw recipients (who received powdered

crude drug 2 g daily for two months) showed significant improvements

in sensitivity to pain and in motility (as measured by

the finger-to-floor distance), compared with placebo recipients.(48)

Several, open, uncontrolled, post-marketing surveillance studies(

49–53) have assessed the effects of devil's claw preparations in patients with

rheumatic and arthritic disorders, and back pain. These studies typically have

reported improvements in pain scores at the end of the treatment period,

compared with baseline values. However, the design of these studies (i.e. no

control group) does not allow any conclusions to be drawn on the effects of

devil's claw in these conditions as there are alternative explanations for the

observed effects.

Another study involved 45 patients with osteo- or rheumatoid arthritis

who received devil's claw root extract 2.46 g daily for two weeks in addition

to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) treatment, followed by devil's

claw extract alone, for four weeks.(54) It was reported that there were no

statistically significant changes in pain intensity and duration of morning stiffness

during the period of treatment with devil's claw extract alone. In subgroups of

patients with rheumatoid arthritis and those with osteoarthritis, small decreases

were observed in concentrations of C-reactive protein and creatinine,

respectively.

The design of this study in terms of the treatment regimen (NSAID

followed by devil's claw extract without a wash-out period), also precludes

definitive conclusions about the effects of devil's claw preparations.

MAIN ACTIONS

Anti-inflammatory/Analgesic

There is good in vitro and in vivo pharmacological evidence of the

anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties of devil’s claw, although some

negative findings have also been reported (McGregor et al 2005).

Overall, greatest activity appears to be in semi-chronic rather than acute

conditions. Devil’s claw exerted significant analgesic effects against

thermally and chemically induced nociceptive pain stimuli in mice and

significant dose-related reduction of experimentally induced acute inflammation

in rats (Mahomed & Ojewole 2004), as well as reducing pain

and inflammation in Freund’s adjuvant- induced arthritis in rats (Andersen

et al 2004). Results from a recent study in mice suggest that the opioid

system is involved in the antinociceptive effects of H. procumbens extract

(Uchida et al 2008).

The iridoids, particularly harpagoside, are thought to be the main

active constituents responsible for the anti-inflammatory activity, although

the mechanism of action is unknown and devil’s claw is also rich in

water-soluble antioxidants (Betancor- Fernandez

et al 2003). More recent in vitro evidence suggests that the

anti-inflammatory effect may in part be due to antioxidant activity (Denner 2007,

Grant et al 2009, Langmead et al 2002).

A study administering H. procumbens extract

intraperitoneally to rats found that the anti-inflammatory response does not

depend on the release of adrenal corticosteroids (Catelan

et al 2006). Contradictory evidence exists as to whether devil’s claw

affects prostaglandin (PG) synthesis. Early in vitro and in vivo studies

suggest that it does not inhibit PG synthesis (Whitehouse et al

1983) and this is supported by studies of PG production in humans (Moussard

et al 1992). However, more recent investigations have suggested that its

anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities are due to suppression of PGE2

synthesis and nitric oxide production and that the herb may suppress

expressions of COX-2 and iNOS (Jang et al 2003).

Harpagoside alone has been shown to suppress COX-2 and iNOS at both the mRNA

and protein level in vitro due to a suppression of NF-kappaB activation (Huang

et al 2006).

Recent in vitro research shows that harpagoside and 8-O-(p-coumaroyl)-harpagide

exhibit a greater reduction in COX-2 expression than verbascoside and that

harpagide on the other hand causes a significant increase in COX-2 expression

(Abdelouahab & Heard 2008a). Additionally, methanolic extracts of devil’s

claw have been shown to inhibit COX-2 in vivo (Kundu et al 2005,

Na et al 2004). Inhibition of leukotriene synthesis has been observed in vitro,

which appears to relate to the amount of harpagoside present (Loew

et al 2001).

A study using subcritical and supercritical CO2 extracts (15 to

30% harpagoside) showed almost total inhibition of 5-lipoxygenase biosynthesis

at 51.8 mg/mL of extract, whereas the

conventional extract (2.3% harpagoside) did not inhibit the enzyme

significantly (Gunther et al 2006).

In vivo experiments have determined that the method of administration

of devil’s claw affects its anti-inflammatory properties. Intraperitoneal and intraduodenal

administration was shown to reduce carrageenan-induced oedema, whereas oral

administration had no effect, suggesting that exposure to stomach acid may

reduce its anti-inflammatory activity (Soulimani et al 1994).

This is supported by a study that found a loss of anti-inflammatory activity

after acid treatment (Bone & Walker 1997). devil’s claw may be used

as an anti-inflammatory agent in the treatment of glomerular inflammatory diseases

(Kaszkin et al 2004a). Devil’s claw extract produced

a concentration-dependent suppression of nitrite formation in rat mesangial

cells in vitro due to an inhibition of iNOS expression through interference

with the transcriptional activation of iNOS. It was found that this activity

was due to harpagoside, together with other constituents that possibly have

strong anti-oxidant activity (Kaszkin et al 2004b). It

has been suggested that the suppression of inflammatory cytokine synthesis,

demonstrated in vitro and vivo (Fiebich et al 2001,

Spelman et al 2006), could explain its therapeutic effect in arthritic inflammation

(Kundu et al 2005). Fiebich and co-workers found that a

60% ethanolic extract decreases the expression of IL-1-beta, IL-6, and TNF-alpha

(Fiebich et al 2001).

Chondroprotective

In

vitro data suggest that the active principles of H. procumbens inhibit not

only inflammatory mediators but also mediators of cartilage destruction, such

as matrix metalloproteinases, NO and elastase (Boje et al 2003,

Schulze-Tanzil et al 2004). A study using an animal model confirmed a chondroprotective

effect in which the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase- 2 is involved (Chrubasik

et al 2006).

Hypoglycaemic

Devil’s

claw extract produced a dose-dependent, significant reduction in the blood

glucose concentrations of both fasted normal and fasted diabetic rats (Mahomed

& Ojewole 2004).

OTHER ACTIONS

In

vitro and in vivo evidence suggests that harpagoside may exhibit cardiac affects

and lower blood pressure, heart rate and reduce arrhythmias (Fetrow

& Avila 1999). As an extremely bitter herb, devil’s claw is thought to increase

appetite and bile production. Diterpenes extracted from the roots and seeds of

devil’s claw exhibited selective antiplasmodial (Clarkson et al 2003)

and antibacterial activity (Weckesser et

al 2007) in vitro, which may have future relevance in view of the increasing

resistance to conventional antimalarials and antibiotics. One study showed that

aqueous devil’s claw extract can markedly delay the onset, as well as reduce

the average duration, of convulsion in mice. Although not conclusive, it seems that

the extract produces its anticonvulsant activity by enhancing GABAergic neurotransmission

and/or facilitating GABAergic action in the brain (Mahomed &

Ojewole 2006).

ACTIVITIES

Allergenic (f; PHR); Analgesic (2; CAN; KOM; MAB;

PH2); Antiarrhythmic (1; APA); Antiarthritic (1; CRC; MAB; PH2; VVG); Antiedemic

(1; BGB); Antiexudative (f; SHT); Antiinflammatory (2; APA; BGB; CRC; KOM;

PH2); Antipyretic (f; HHB); Antirheumatic (1; CAN; MAB); Aperitif (2; APA; HH2;

KOM; VAG); Bitter (1; APA; MAB; PED); Choleretic (2; HH2; KOM; PH2); Depurative

(f; BGB; PED); Digestive (f; SKY); Diuretic (f; CAN); Hypocholesterolemic (1;

CRC; PED; VAG); Hypotensive (1; APA; BGB); Hypouricemic (1; CRC; PED; VAG);

Laxative (f; MAB; WBB); Secretagogue (1; PH2); Sedative (f; CAN); Tonic (1;

APA; MAB; VVG); Uricolytic (1; APA); Uterocontractant (f; VAG).

INDICATIONS

Aging (f; CRC); Allergy (1; BGB; CRC; MAB; PH2);

Anorexia (2; APA; HH2; KOM; PH2; SHT; VAG); Arrhythmia (1; APA; BGB; MAB);

Arthrosis (2; APA; CRC; KOM; MAB; PH2; VVG); Atherosclerosis (f; CRC); Backache

(2; BGB; BRU; MAB; PHR); Blood (f; BGB); Boil (1; BGB; CRC; MAB; VVG); Bursitis

(f; WAF); Cancer (f; APA; WBB); Cancer, skin (f; CRC); Cardiopathy (1; MAB);

Childbirth (1; APA; BRU; CRC; MAB; VAG; WBB); Cholecystosis (2; CRC; PHR; PH2);

CNS (f; PH2); Cramp (f; VAG); Cystosis (f; CRC; HHB; PH2); Dermatosis (f; BGB;

PHR); Diabetes (f; CRC; HHB; VAG); Dysmenorrhea (1; CRC; VAG); Dyspepsia (2;

APA; BGB; CRC; KOM; PH2; SHT); Edema (1; BGB); Enterosis (f; BRU; CRC); Fever

(1; APA; BGB; BRU; HHB; VAG); Fibromyalgia (f; WAF); Fibrosis (1; CAN; VAG); Gastrosis

(f; BRU; CRC); Gout (1; CAN; CRC; VAG); Headache (1; APA; BGB; MAB); Heartburn (2;

CRC; KOM; SKY); Hepatosis (2; CRC; PHR; PH2); High Blood Pressure (1; APA; BGB;

VAG); High Cholesterol (1; CRC; PED; VAG); Inflammation (2; APA; BGB; CRC; KOM;

MAB; PH2); Insomnia (f; CAN); Lumbago (1; BGB; CAN; CRC); Migraine (1; MAB);

Myalgia (f; CAN); Nephrosis (f; CRC; HHB; PH2); Nervousness (f; CAN); Neuralgia

(1; BGB; CRC); Neurosis (f; PH2); Osteoarthrosis (1; VAG); Pain (2; APA; BGB;

CAN; KOM; MAB; PHR; PH2; VVG); Parturition (f; VVG); Pleurodynia (f; CAN);

Pregnancy (f; APA; PH2); Rheumatism (2; CAN; KOM; MAB; PHR; PH2); Sore (1; BGB;

CRC; MAB; VVG); Swelling (1; BGB); Tendinitis (1; BGB; WAF); Tuberculosis (f;

VAG); Ulcer (f; CRC; MAB); Water Retention (f; CAN); Wound (f; CRC; PHR).

I suppose that Commission E is talking about various

degenerative arthritic conditions when they approve this for, “Supportive

therapy of degenerative disorders of the locomotor system,” but just couldn’t

bring themselves around to saying arthrosis, or degenerative joints and/or

muscles (KOM).

INDICATIONS AND

USAGE

Approved by

Commission E:

• Dyspeptic complaints

• Loss of appetite

• Rheumatism

Unproven Uses: In folk medicine,

Devil's Claw is used as an ointment for skin injuries and disorders. The dried

root is used for pain relief; pregnancy discomforts; arthritis; allergies; metabolic

disorders; and kidney, bladder, liver and gallbladder disorders. In South Africa

it is used for fevers

and

digestive disorders. Devil's Claw is also used for supportive

therapy of degenerative disorders of the CNS system.

Homeopathic Uses:

Chronic

rheumatism is the primary use for Devil's Claw in homeopamy.

PRODUCT AVAILABILITY

Capsules, Dried Powdered Root, Dry

Solid Extract, Tea, Tincture

PLANT PARTS USED: ROOTS, Tubers (Secondary Root Tuber)

DOSAGES

DOSAGES

Anorexia

·

Adult PO infusion: 1.5 g herb

tid (Blumenthal, 1998)

Gout

·

Adult PO dried powdered root:

1-2 g tid (Murray, Pizzorno, 1998)

·

Adult PO tincture: 4-5 mL (1:5 dilution) tid (Murray, Pizzorno, 1998)

·

Adult PO dry solid extract: 400

mg tid (Murray, Pizzorno, 1998)

Osteoarthritis

·

Adult PO dried powdered root:

1-2 g tid (Murray, Pizzorno, 1998)

·

Adult PO tincture: 4-5 mL (1:5 dilution) tid (Murray, Pizzorno, 1998)

·

Adult PO dry solid extract: 400

mg tid (Murray, Pizzorno, 1998)

Other

·

Adult PO infusion: _4.5 g herb (Blumenthal, 1998) in 300 mL boiling water, let stand 8 hr, strain and

drink

DOSAGES

Dosages

for oral administration (adults) recommended in older and more contemporary

standard herbal reference texts are given below.

Painful Arthrosis and Tendonitis

·

1.5–3 g dried tuber as a decoction, three times daily; 1–3 g

drug or equivalent aqueous or hydroalcoholic extracts;(G76)

·

Liquid Extract 1–3mL (1 :

1, 25% ethanol) three times daily.(G6)

Loss Of Appetite Or Dyspepsia

·

Dried Tuber 0.5 g as a decoction, three times

daily.(G6)

·

Tincture 1

mL (1 : 5, 25% ethanol) three times

daily.(G6)

Clinical

trials of devil's claw root extracts for the treatment of low back pain

typically have tested oral doses ranging from 2000– 4500 mg daily, in two or

three divided doses (equivalent to less than 30 mg up to 100 mg harpagoside

daily, depending on the particular extract), for four to 20 weeks.(13) In a

clinical trial in osteoarthritis, participants received capsules containing

powdered cryoground devil's claw root 2610 mg daily for four months.(14)

DOSAGES

·

1 tsp chopped root/2 cups water, sipped through day (APA); 1.5–4.5(–10)

g root (KOM; SHT; SKY);

·

6 g root/day (MAB); 1–2 tsp fresh root (PED); 0.5–1 g dry root

(PED);

·

1 g dry root:5 mL alcohol/5 mL water (PED); 0.1–0.25 g powdered tuber (PNC);

·

0.1–0.25 g dry tuber as tea 3 x/day (CAN); 0.1–0.25 mL liquid extract (1:1 in 25% ethanol) 3 x /day (CAN);

·

6–12 mL liquid extract

(1:2)/day (MAB); 15–30 mL tincture

(1:5)/day (MAB);

·

0.5–1 mL root tincture

(1:5 in 25% alcohol) 3 x /day (CAN).

DOSAGES

Musculoskeletal Conditions

·

Dried root or equivalent

aqueous or hydroalcoholic extracts: 2–6 g daily for painful arthritis; 4.5–9 g

daily for lower back pain.

·

Liquid extract (1:2):

6–12 mL /day.

·

Tincture (1:5): 2–4 mL

three times daily.

It is suggested that devil’s claw extracts with at least 50 mg

harpagoside in the daily dosage should be recommended for the treatment of pain

(Chrubasik 2004a, 2004b).

Digestive Conditions (e.g. dyspepsia)

·

Dosages equivalent to

1.5 g/day dried herb are used (Blumenthal et al

2000). It is suggested that devil’s claw

preparations be administered between meals, when gastric activity is reduced.

DOSAGES

MODE

OF ADMINISTRATION: As comminuted drug for infusions and

other preparations for internal use, as an ointment for external use.

HOW SUPPLIED:

•

Capsules

— 405 mg, 480 mg, 510 mg, 520 mg

•

Tablets

PREPARATION: To make an

infusion, use 1 teaspoonful (equivalent to 4.5 g) comminuted drug with 300 mL boiling water. Steep for 8 hours and strain.

DAILY

DOSAGE:

for

loss of appetite, the recommended dosage is 1.5 g of drug; otherwise 4.5 g of

drug is used. The infusion can be taken 3 times a day.

HOMEOPATHIC

DOSAGE:

5

to 10 drops, 1 tablet or 5 to 10 globules 1 to 3 times a day, or from D3 1 mL injection solution sc twice weekly (HAB1). The

ointment is applied 1 to 3 times a day. For external use, 1 dessertspoon of the

tincture should be diluted with 250 mL and used for washes or poultices.

STORAGE: Store Devil's

Claw in a container that protects it from light and moisture.

PRECAUTIONS AND ADVERSE REACTIONS

Health

risks or side effects following the proper administration of designated

therapeutic dosages are not recorded. The drug has a sensitizing effect.

Devil’s claw is a well tolerated treatment. In a recent review of

28 clinical trials it was found that only minor adverse events, mainly mild

gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g. diarrhoea), occur in 3% of the patients. The incidence

of adverse effects in the treatment groups was never higher than in the placebo

groups for all 28 trials (Vlachojannis et al 2008).

Use cautiously in patients with gastric and duodenal ulcers,

gallstones or acute diarrhoea, as devil’s claw may cause gastric irritation (Blumenthal

et al 2000).

CONTRAINDICATIONS, INTERACTIONS, AND SIDE EFFECTS

CLASS 2B, 2D (AHP). Contraindicated in duodenal and gastric

ulcers (AHP, 1997). Commission E reports contraindications in GI ulcer (AEH).

Contraindicated in people with diabetes. Excessive doses may interfere with blood

pressure and cardiac therapy (CAN). LD50 = >13,500 mg/kg orl mouse (CAN).

CONTRA-INDICATIONS,

WARNINGS

Devil's claw is stated to be contra-indicated in gastric and duodenal

ulcers,(G3, G76) and in gallstones should be used only after consultation with

a physician.(G3)

Drug Interactions None have been described for devil's claw preparations.

However, on the basis of pharmacological evidence of devil's claw's

cardioactivity, the possibility of excessive doses interfering with existing

treatment for cardiac disorders or with hypo/hypertensive therapy should be

considered. Inhibitory effects on certain cytochrome P450 (CYP) drug

metabolising enzymes have been documented for a devil's claw root extract

(Bioforce) in vitro using a technique involving liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

and automated online extraction.(58) Mean (standard deviation) IC50 values for

the devil's claw extract when tested in assays with individual CYP enzymes were

997 (23), 254 (17), 121 (8), 155 (9), 1044 (80) and 335 (14) for the CYPs 1A2,

2C8, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6 and 3A4, respectively.

Pregnancy And Lactation It

has been stated that devil's claw has oxytocic properties,(59) although the

reference gives no further details and the basis for this statement is not

known. In addition, there is no further evidence to substantiate the statement.

However, given the lack of data on the effects of devil's claw taken during

pregnancy and lactation, its use should be avoided during these periods.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

The drug should

not be used in the presence of stomach or duodenal ulcers, due to the drug's stimulation

of gastric juice secretion.

PREGNANCY USE

Devil’s claw is

not recommended in pregnancy, as it has exhibited oxytocic activity in animals.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Pregnancy category is 3;

Breastfeeding category is 2A. Until more research is available,

this herb should not be given to children. Persons with peptic or duodenal

ulcer disease, cholecystitis, or hypersensitivity to this herb should avoid the

use of devil’s claw.

SIDE EFFECTS/ADVERSE REACTIONS

CNS: Headache

CV: Hypotension

EENT: Tinnitus

GI: Nausea,

vomiting, anorexia

INTEG: Hypersensitivity

reactions

INTERACTIONS

Drug

Antacids, H2-blockers, proton pump inhibitors: Devil’s claw may decrease the action of these agents

(Jellin et al, 2008).

Antiarrhythmics, antihypertensives: Because two of the chemical components in devil’s claw

exert inotropic and chronotropic effects, use this herb cautiously with

antiarrhythmics and antihypertensives (theoretical).

Antidiabetics: Devil’s

claw may cause an additive effect with antidiabetics (Jellin et al, 2008).

Warfarin: Devil’s

claw taken with warfarin may cause risk of bleeding (Jellin et al, 2008).

Lab Test

APTT, PT: Devil’s

claw may increase these levels.

SIGNIFICANT INTERACTIONS

Devil’s

claw has been found to moderately inhibit cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP2C9,

2C19, 3A4) in vitro (Unger & Frank 2004), however, the clinical relevance

of this is yet to be determined. In contrast to NSAIDs, devil’s claw does not

affect platelet function (Izzo et al 2005).

Warfarin

Rare

case reports suggest that devil’s claw may potentiate the effects of warfarin,

but the reports are mostly inconclusive (Argento et al 2000, Heck

et al 2000, Izzo et al 2005). Clinical testing would be

required to confirm a possible interaction.

Anti-arrythmic

Drugs

Theoretical

interaction exists when the herb is used in high doses; however, clinical

testing is required to determine significance — observe patients taking concurrent

antiarrythmics (Fetrow & Avila 1999).

EFFECTS

Devil's Claw

stimulates gastric juice secretion and is choleretic. Anti-inflammatory, analgesic

(and tiius anti-arthritic) effect has been shown in animal experiments.

TOXICITY

The

acute LD50 of devil’s claw was more than 13.5 g/kg according to one study (Bone

& Walker 1997). In a recent review of 28 clinical trials only a few reports on

acute toxicity were found, whereas no reports on chronic toxicity had been

reported. The review concluded that more studies for longterm treatment are

needed (Vlachojannis et al 2008).

An earlier review looking at 14 clinical trials had come to the same conclusion

(Brien et al 2006).

SIDE-EFFECTS, TOXICITY

The

mechanism of action of devil's claw remains unclear, in particular, whether it

has significant effects on the mediators of acute inflammation. Data from in

vitro and clinical studies in this regard do not yet give a clear picture (see Pharmacological

Actions, In vitro and animal studies and Clinical studies, Pharmacodynamics).

It has been stated that adverse effects associated with the use of NSAIDs are

unlikely to occur with devil's claw, even during long-term treatment.(G50, G76)

While there are no documented reports of gastrointestinal bleeding or peptic

ulcer associated with the use of devil's claw, the latter statement requires

confirmation. Use of devil's claw in gastric and duodenal ulcer is

contraindicated, although this appears to be because of the drug's bitter

properties.(G50)

CLINICAL DATA

Randomised,

placebo-controlled trials involving patients with rheumatic and arthritic

conditions who have received devil's claw extracts or powdered drug at approximately

recommended doses for four weeks have reported mild, transient gastrointestinal

symptoms (such as diarrhoea, flatulence) in a small proportion (less than 10%)

of devil's claw recipients.(43–45) No serious adverse events were reported,

although one patient withdrew from one study because of tachycardia.(43)

A small number of reports of randomised trials comparing the effects

of devil's claw preparations with those of standard pharmaceutical agents has

included data on adverse events. In a randomised, double-blind, pilot trial, 88

participants with acute exacerbations of low back pain received an aqueous

extract of devil's claw (Doloteffin; drug to extract ratio 1.5-2.5:1) 2400 mg daily

in three divided doses (equivalent to 60 mg harpagoside daily), or rofecoxib

(Vioxx) 12.5 mg daily for six weeks.(46) In total, 28 (32%) participants (14 in

each group) experienced adverse events, most commonly gastrointestinal

complaints (9 in each group).

In a follow-up study, participants in the six-week pilot study were

offered continuing treatment with devil's claw aqueous extract two tablets

three times daily for up to one year. Participants were not aware of their

initial study group (i.e. devil's claw extract or rofecoxib) until towards the

end of the oneyear follow-up study.(47) In total, 38 and 35 participants who

had previously received devil's claw and rofecoxib, respectively, participated

in the follow-up study and, after 24 and 54 weeks, a total of 53 and 43

participants, respectively, remained in the study. Overall, 17 (23%) of the 73

participants in the follow-up study experienced a total of 21 adverse events.

Of these, the causality for three events was classified (by a physician not involved

in the study) as 'likely' (one allergic skin reaction) or 'possible'

(diarrhoea, acid 'hiccup') with respect to devil's claw treatment. Five

participants (7%) withdrew from the study because of adverse events. In a

randomised, controlled trial comparing devil's claw extract with diacerein in

patients with osteoarthritis, numbers of patients ending the study prematurely

because of suspected adverse drug reactions were 8 and 14 for devil's claw and

diacerein recipients, respectively.(14) In total, 26 diacerein recipients and

16 devil's claw recipients reported one or more adverse events (p = 0.042). The

numbers of adverse events attributed to the treatment was significantly lower

for devil's claw than for diacerein (10 versus 21; p = 0.017). The most frequently

reported adverse event, diarrhoea, occurred in 8.1% and 26.7% of devil's claw

and diacerein recipients, respectively.

Several, open, uncontrolled studies,(51–53) which have assessed the

effects of devil's claw preparations in patients with arthritic disorders and

back pain, have reported data on adverse events. In an open, uncontrolled,

multicentre, surveillance study involving patients with arthrosis of the hip or

knee, 75 participants received tablets containing an aqueous extract of the

secondary tubers of devil's claw (Doloteffin; drug extract ratio = 1.5-2.5 : 1)

at a dosage of two 400 mg tablets three times daily (equivalent to 50 mg

iridoidglycosides, calculated as harpagoside) for 12 weeks.(51) During the

study, four (5%) participants experienced adverse events (dyspeptic complaints,

2; sensation of fullness, 1; panic attack, 1), although none stopped treatment

with devil's claw. Causality was assessed as 'possible' for two of these events.

In a similar open, uncontrolled, multicentre study, 130 participants

with chronic non-radicular back pain received tablets containing 480 mg devil's

claw extract (LI-174; drug extract ratio = 4.4-5 : 1) at a dosage of one tablet

twice daily for eight weeks.(52)

Overall, 13 (10%) participants withdrew from the study for various

reasons, including no apparent improvement in their condition. No serious

adverse events were reported, but three partipants reported minor adverse

events (bloating, insomnia and outbreaks of sweating). In a post-marketing

surveillance study, 250 patients with non-specific low back pain or

osteoarthritic pain of the knee or hip received an aqueous extract of H. procumbens (Doloteffin) at an oral

dose equivalent to harpagoside 60 mg daily in three divided doses for eight

weeks in addition to any existing treatment and/or additional analgesic

medicines as required. Fifty participants experienced adverse events; most

commonly gastrointestinal complaints (n = 22); two participants experienced allergic

skin reactions.(53) In 27 participants, the adverse event was considered by an

independent investigator to be possibly (n = 11), likely (15) or certainly (1)

related to ingestion of devil's claw.

In another open, uncontrolled study, one patient withdrew after four

days' treatment with devil's claw aqueous extract 1.23 g daily because of

several symptoms, including frontal headache, tinnitus, anorexia and loss of

taste.(55)

There is an isolated report of conjunctivitis, rhinitis and respiratory

symptoms in a 50-year-old woman who had experienced chronic occupational

exposure to devil's claw.(56)

PRECLINICAL DATA

Acute

and subacute toxicity tests in rodents have demonstrated low toxicity of

devil's claw extracts. In a study in mice, the acute oral lethal dose (LD) LD0

and LD50 were greater than 13.5 g/kg body weight.(23) In rats, clinical,

haematological and gross pathological findings were unremarkable following

administration of devil's claw extract 7.5 g/kg by mouth for seven days.

Hepatic effects (liver weight, and concentrations of microsomal protein and

several liver enzymes) were not observed following oral treatment with devil's

claw extract 2 g/kg for seven days.(23) Other studies in mice have reported

acute oral acute intravenous LD0 values of greater than 4.64 g/kg and greater

than 1 g/kg, respectively.(57) For an extract containing harpagoside 85%, acute

oral LD0, acute intravenous LD0 and acute intravenous LD50 values were greater

than 4.64 g/kg, 395 mg/kg and 511 mg/kg, respectively.(57)

CLIENT CONSIDERATIONS

ASSESS

·

Assess for hypersensitivity

reactions. If present, discontinue use of devil’s claw and administer

antihistamine or other appropriate therapy.

·

Assess cardiac status in any

client with a cardiac condition: blood pressure, character of pulse.

·

Identify what prescription

drugs and herbal supplements the client is taking to treat this condition (see

Interactions).

·

Assess joint pain and infl

ammation in any client with an arthritic condition: pain location, duration,

intensity, and alleviating and aggravating factors.

ADMINISTER

·

Instruct the client to store

devil’s claw products in a cool, dry place, away from heat and moisture.

TEACH CLIENT/FAMILY

·

Inform the client that

pregnancy category is 3 and breastfeeding category is 2A.

·

Caution the client not to use

devil’s claw in children until more research is available.

PRACTICE POINTS/PATIENT COUNSELLING

·

Devil’s

claw reduces pain and inflammation and is a useful treatment in arthritis and

back pain, according to controlled studies.

·

The

anti-inflammatory action appears to be different to that of NSAIDs and has not

been fully elucidated. There is also preliminary evidence of a

chondroprotective effect.

·

Preliminary

research suggests that it is best to take devil’s claw between meals, on an

empty stomach.

·

Devil’s

claw appears to be relatively safe but should not be used in pregnancy and

should be used with caution in people with ulcers or gallstones

or in those taking warfarin.

PATIENTS’ FAQs

What

will this herb do for me?

Devil’s claw is a useful

treatment for arthritis and back pain. It may also increase appetite and

improve digestion and dyspepsia.

When

will it start to work?

Results from studies suggest

that pain-relieving effects will start within 4–12 weeks reaching maximum pain

relief after 3–4 months (Chrubasik S et al 2007, Thanner et al 2008).

Are

there any safety issues?

Devil’s claw should be used

cautiously by people with gallstones, diarrhoea, stomach ulcers and those taking

the drug warfarin. It is also not recommended in pregnancy.

PREPARATIONS

PROPRIETARY SINGLE-INGREDIENT

PREPARATIONS

France:

Harpadol; Harpagocid. Germany: Ajuta; Allya; Arthrosetten H; Arthrotabs;

Bomarthros; Cefatec; Dolo- Arthrodynat; Dolo-Arthrosetten H; Doloteffin;

flexi-loges; Harpagoforte Asmedic; HarpagoMega; Harpagosan; Jucurba; Matai;

Pargo; Rheuferm Phyto; Rheuma-Sern; Rivoltan; Sogoon; Teltonal; Teufelskralle.

Spain: Fitokey Harpagophytum; Harpagofito Orto.

PROPRIETARY MULTI-INGREDIENT

PREPARATIONS

Australia:

Arthriforte; Arthritic Pain Herbal Formula 1; Bioglan Arthri Plus; Boswellia

Compound; Devils Claw Plus; Extralife Arthri-Care; Guaiacum Complex; Herbal

Arthritis Formula; Lifesystem Herbal Formula

1 Arthritic Aid; Prost-1. Czech Republic: Antirevmaticky Caj. France: Arkophytum.

Germany: Dr Wiemanns Rheumatonikum. Italy: Bodyguard; Nevril; Pik Gel.

Malaysia: Celery Plus. Spain: Dolosul; Natusor Harpagosinol.

EXTRACTS

German

clinical studies confirm arthritic relief; hypocholesterolemic, hypouricemic

(PED). Chrubasik et al. (1996) studied the effectiveness in treatment of

acute low back pain. While animal studies exhibit analgesic and

antiinflammatory activities (due to harpagoside), this study of 118 patients

with nonspecific low-back pain (most for more than 15 years),with 400 mg

extract 3 ×/day (equivalent of 6000 mg crude root extract = 50 mg harpagoside).

Only 9 of the treated patients improved cf 1 in the placebo controls. The

insignificant reduction in pain was confined to those whose pain did not

radiate to one or both legs. “There was a notable absence of identifiable

clinical, hematological, or biochemical side effects” (PHM3:1). None of these

authors commented on the presence of 3 COX-2 inhibitors as well, kaempferol,

oleanolic acid, and ursolic acid.

REFERENCE

Barnes, J., Anderson, L. A., and Phillipson, J. D. 2007. Herbal

Medicines Third Edition. Pharmaceutical Press. Auckland and

London.

Braun

Duke, J. A. with Mary Jo Bogenschutz-Godwin, Judi duCellier, Peggy-Ann K.

Duke. 2002. Handbook of Medicinal Herbs 2nd Ed. CRC Press

LLC. USA.

Gruenwald, J., Brendler,

T., Jaenicke, Ch. 2000. PDR for Herbal

Medicines. Medical Economics Company, Inc. at Montvale, NJ

07645-1742. USA

Linda S-Roth. 2010. Mosby’s Handbook Of Herbs & Natural

Supplements, Fourth Edition. Mosby Elsevier. USA